2025-09-27 18:13:38

In the architecture of modern computing, while processors, graphics cards, and storage drives often claim the spotlight, the humble Computer Signal Cable performs the critical, albeit less glamorous, task of data transmission. Essentially, a computer signal cable is a specialized assembly of one or more conductors (wires) housed within an insulating jacket, engineered specifically to carry electronic signals—both digital and analog—between components with high fidelity and minimal loss. Unlike power cables designed to deliver electrical current, signal cables are optimized for preserving the integrity of the information being transmitted, which is a complex waveform representing binary data, video signals, or audio streams. The design and construction of these cables are paramount to the performance, reliability, and speed of entire computer systems, from a simple desktop setup to vast data center infrastructures.

The efficacy of a computer signal cable is determined by a set of interrelated electrical and physical characteristics. Each characteristic is backed by precise engineering data that defines its performance envelope.

This is arguably the most cited specification. Bandwidth, measured in megahertz (MHz) or gigahertz (GHz), refers to the range of frequencies the cable can transmit effectively. It directly influences the maximum data rate, expressed in gigabits per second (Gbps). For instance, a standard HDMI 2.1 cable is rated for a bandwidth of up to 48 Gbps, enabling it to support 8K resolution at high refresh rates. Higher bandwidth allows for more data to be pushed through the cable per unit of time, which is essential for high-resolution video, fast storage devices, and high-speed networking.

Impedance, measured in ohms (Ω), is the effective resistance a cable presents to an alternating current (AC) signal. Maintaining a consistent impedance along the entire length of the cable is crucial to prevent signal reflections, which cause distortion and data errors. For example, USB Cables are typically designed for a characteristic impedance of 90 Ω, while many video cables like those used for professional SDI video operate at 75 Ω. Mismatched impedance at connection points is a primary cause of signal degradation.

External electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio-frequency interference (RFI) can corrupt delicate data signals. To combat this, signal cables employ various shielding techniques. A common measure is the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), where a higher value is better. Shielded Twisted Pair (STP) Ethernet cables, for example, use a foil shield around each pair of wires and sometimes a braided shield overall, achieving an attenuation-to-crosstalk ratio (ACR) far superior to unshielded (UTP) cables, which is critical in electrically noisy environments. Crosstalk, specifically quantified as Near-End Crosstalk (NEXT) and Far-End Crosstalk (FEXT) in decibels (dB), measures the amount of signal bleeding from one wire pair to another within the same cable; better shielding and twisting reduce crosstalk.

Also known as insertion loss, attenuation is the gradual loss of signal strength as it travels along the cable. It is frequency-dependent and measured in decibels per unit length (e.g., dB/m or dB/100ft). Higher-quality cables with thicker conductors and superior dielectric materials exhibit lower attenuation. For a Category 6A Ethernet cable, the attenuation at 250 MHz must not exceed 43.1 dB per 100 meters. Exceeding the maximum recommended length for a cable standard (e.g., 100 meters for Ethernet) often results in attenuation that makes the signal unrecognizable at the receiver.

The material and thickness of the internal conductors significantly impact resistance and signal quality. Oxygen-Free High Conductivity (OFHC) copper is standard, offering low resistance. Higher-end cables may use silver-plated copper for even better high-frequency performance. The gauge of the wire, denoted by the American Wire Gauge (AWG) number, defines its diameter. A lower AWG number indicates a thicker wire (e.g., 24 AWG is thicker than 28 AWG). Thicker conductors have lower DC resistance, which reduces voltage drop and power loss, a critical factor for bus-powered devices like external hard drives.

While often negligible in short cables, latency (signal propagation delay) becomes a factor in very long runs, such as in large data centers, where a delay of a few nanoseconds per meter can add up. Furthermore, in cables with multiple pairs for differential signaling (like DVI or HDMI), skew is the difference in arrival time between signals on different pairs. High skew can cause synchronization issues, leading to visual artifacts; premium cables are engineered to minimize skew to within a few picoseconds.

The specific design of a signal cable dictates its ideal application, leading to a diverse ecosystem of cable types.

Display Connectivity: Cables like High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI), DisplayPort (DP), and Digital Visual Interface (DVI) are engineered for high-bandwidth, uncompressed video and audio transmission. They are indispensable in home theaters, gaming rigs, professional graphic design workstations, and digital signage. DisplayPort 2.1, for example, supports data rates up to 80 Gbps, targeting future high-resolution monitors and virtual reality systems.

Data Transfer and Peripheral Connection: Universal Serial Bus (USB) cables, from USB 2.0 (480 Mbps) to the latest USB4 (40 Gbps), are the universal standard for connecting a vast array of peripherals—keyboards, mice, printers, external storage (SSDs and HDDs), and smartphones. Thunderbolt™ technology, which often uses the USB-C connector, pushes data rates even further, merging data, video, and power delivery into a single cable.

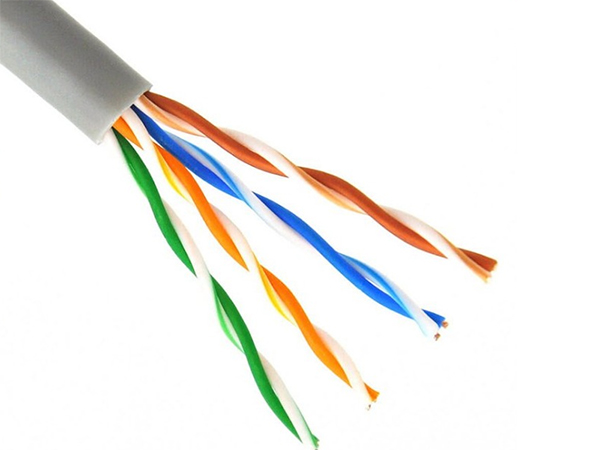

Networking: Ethernet cables (e.g., Category 5e, 6, 6A, 8) form the physical backbone of Local Area Networks (LANs) and the internet itself. These twisted-pair cables are rated for speeds from 1 Gbps (Cat 5e) up to 40 Gbps (Cat 8) over short distances, connecting computers, switches, and routers in homes, offices, and data centers.

Internal Computer Connections: Inside a computer case, Serial ATA (SATA) cables connect storage drives to the motherboard, with SATA III supporting speeds up to 6 Gbps. Similarly, delicate ribbon cables or finely pitched wires connect front-panel controls, internal USB headers, and other components to the mainboard.

Audio-Visual Production: In professional settings, cables like SDI (Serial Digital Interface) are used for broadcast-quality video due to their robust locking connectors and ability to run signals over long distances (up to 100 meters or more with the right cable grade) without significant loss.

To ensure optimal performance and extend the operational life of Computer Signal Cables, a regimen of proper care is essential. Neglect can lead to intermittent connections, reduced data speeds, and complete failure.

Avoid Sharp Bends and Kinks: The most critical rule is to never bend a cable sharply, especially near the connectors. A tight bend radius, typically recommended to be no less than five times the diameter of the cable, can permanently damage the internal conductors and shielding, changing the cable's impedance and causing signal reflection. For instance, sharply bending a Coaxial Cable can crush its dielectric insulator, leading to significant signal loss.

Manage Strain Relief: Always use the cable's built-in strain relief. When plugging and unplugging, grip the connector housing firmly, not the cable itself. Tugging on the cable puts stress on the internal solder joints, which can break over time. For permanent installations, use cable ties or Velcro straps to secure cables loosely, avoiding points of high tension.

Prevent Physical Damage: Keep cables away from areas where they might be pinched by furniture, rolled over by chairs, or chewed by pets. Routing cables under carpets can eventually crush them, while running them over door frames or sharp edges can cut through the insulation. Using cable protectors or conduits in high-traffic areas is a prudent measure.

Ensure Clean and Secure Connections: Periodically inspect connectors for dust, debris, or oxidation, which can increase resistance and interfere with the signal. Connectors can be gently cleaned with isopropyl alcohol and a soft cloth. Ensure connectors are fully seated in their ports; a loose connection is a common source of problems. However, avoid frequently plugging and unplugging, as this wears out the contacts.

Proper Coiling for Storage: When not in use, cables should be coiled loosely using the "over-under" technique instead of wrapping them tightly around an object. The over-under method prevents the cable from developing a permanent twist or kink that can damage internal wires. Store coils in a dry, temperate environment away from direct sunlight, which can degrade the plastic insulation over many years.

Respect Length Limitations: Always be aware of the maximum effective length for a given cable standard. Using an active cable (one with built-in signal amplification chips) or a signal booster is necessary for runs that exceed the passive length limitations, such as when needing an HDMI signal to travel more than 15 meters without degradation.

In conclusion, the computer signal cable is a masterpiece of precision engineering, where every material choice and design parameter is optimized for a specific type of information transfer. Understanding its technical characteristics allows users to select the right cable for the task, while diligent maintenance ensures that the vital flow of data remains uninterrupted, securing the seamless operation of our interconnected digital world.

Specializing in the production of wire and cable Hong Kong funded enterprises (both domestic and foreign sales); has won the IS09001-2000 international quality certification and the United States UL safety certification, is a professional wire manufacturers.

Tel: +86-769-8178 1133

Mobile: +86-13549233111

E-mail: andy@herwell.com.cn

Add: No.13 Shui Chang Er Road, Shui Kou Village, Dalang Town, Dongguan City, Guangdong Province, China